Hearing the shape of a drum

To hear the shape of a drum is to infer information about the shape of the drumhead from the sound it makes, i.e., from the list of basic harmonics, via the use of mathematical theory. "Can One Hear the Shape of a Drum?" was the witty title of an article by Mark Kac in the American Mathematical Monthly 1966 (see the references below), but these questions can be traced back all the way to Hermann Weyl.

The frequencies at which a drumhead can vibrate depend on its shape. The Helmholtz equation tells us the frequencies if we know the shape. These frequencies are the eigenvalues of the Laplacian in the region. A central question is: can they tell us the shape if we know the frequencies? No other shape than a square vibrates at the same frequencies as a square. Is it possible for two different shapes to yield the same set of frequencies? Kac did not know the answer to that question.

Contents |

Formal statement

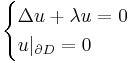

More formally, the drum is conceived as an elastic membrane whose boundary is clamped. It is represented as a domain D in the plane. Denote by λn the Dirichlet eigenvalues for D: that is, the eigenvalues of the Dirichlet problem for the Laplacian:

Two domains are said to be isospectral (or homophonic) if they have the same eigenvalues. The term "homophonic" is justified because the Dirichlet eigenvalues are precisely the fundamental tones that the drum is capable of producing: they appear naturally as Fourier coefficients in the solution wave equation with clamped boundary.

Therefore the question may be reformulated as: what can be inferred on D if one knows only the values of λn? Or, more specifically: are there two distinct domains that are isospectral?

Related problems can be formulated for the Dirichlet problem for the Laplacian on domains in higher dimensions or on Riemannian manifolds, as well as for other elliptic differential operators such as the Cauchy–Riemann operator or Dirac operator. Other boundary conditions besides the Dirichlet condition, such as the Neumann boundary condition, can be imposed. See spectral geometry and isospectral as related articles.

The answer

Almost immediately, John Milnor observed that a theorem due to Ernst Witt implied the existence of a pair of 16-dimensional tori that have the same eigenvalues but different shapes. However, the problem in two dimensions remained open until 1992, when Gordon, Webb, and Wolpert constructed, based on the Sunada method, a pair of regions in the plane that have different shapes but identical eigenvalues. The regions are non-convex polygons (see picture). The proof that both regions have the same eigenvalues is rather elementary and uses the symmetries of the Laplacian. This idea has been generalized by Buser et al., who constructed numerous similar examples. So, the answer to Kac's question is: for many shapes, one cannot hear the shape of the drum completely. However, some information can be inferred.

On the other hand, Steve Zelditch proved that the answer to Kac's question is positive if one imposes restrictions to certain convex planar regions with analytic boundary. It is not known whether two non-convex analytic domains can have the same eigenvalues. It is known that the set of domains isospectral with a given one is compact in the C∞ topology. Moreover, the sphere (for instance) is spectrally rigid, by Cheng's eigenvalue comparison theorem. It is also known, by a result of Osgood, Phillips, and Sarnak that the moduli space of Riemann surfaces of a given genus does not admit a continuous isospectral flow through any point, and is compact in the Frechet–Schwartz topology.

Weyl's formula

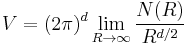

Weyl's formula states that one can infer the area V of the drum by counting how rapidly the λn grow. We define N(R) to be the number of eigenvalues smaller than R and we get

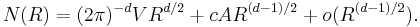

where d is the dimension. Weyl also conjectured that the next term in the approximation below would give the perimeter of D. In other words, if A denotes the length of the perimeter (or the surface area in higher dimension), then one should have

where c is some constant that depends only on the dimension. For smooth boundary, this was proved by Victor Ivrii in 1980.

The Weyl–Berry conjecture

For non-smooth boundaries, Michael Berry conjectured in 1979 that the correction should be of the order of

where D is the Hausdorff dimension of the boundary. This was disproved by J. Brossard and R. A. Carmona, who then suggested one should replace the Hausdorff dimension with the upper box dimension. In the plane, this was proved if the boundary has dimension 1 (1993), but mostly disproved for higher dimensions (1996). Both results are by Lapidus and Pomerance.

See also

References

- Arrighetti, W.; Gerosa, G. (2005), "Can you hear the fractal dimension of a drum?", Applied and Industrial Mathematics in Italy, Series on Advances in Mathematics for Applied Sciences, 69, World Scientific, pp. 65–75, arXiv:math.SP/0503748, ISBN 978-981-256-368-2

- Brossard, Jean; Carmona, René (1986), "Can one hear the dimension of a fractal?", Comm. Math. Phys. 104 (1): 103–122, doi:10.1007/BF01210795

- Buser, Peter; Conway, John; Doyle, Peter; Semmler, Klaus-Dieter (1994), "Some planar isospectral domains", International Mathematics Research Notices 9: 391ff

- Chapman, S.J. (1995), "Drums that sound the same", American Mathematical Monthly (February): 124–138

- Giraud, Olivier; Thas, Koen (2010). "Hearing shapes of drums - mathematical and physical aspects of isospectrality". Reviews of Modern Physics 82 (3): 2213–2255. arXiv:1101.1239. doi:10.1103/RevModPhys.82.2213.

- Gordon, Carolyn; Webb, David, "You can't hear the shape of a drum", American Scientist 84 (January–February): 46–55

- Gordon, C.; Webb, D.; Wolpert, S. (1992), "Isospectral plane domains and surfaces via Riemannian orbifolds", Inventiones mathematicae 110 (1): 1–22, doi:10.1007/BF01231320

- Gordon, Carolyn; Webb, David L.; Wolpert, Scott (1992), "One Cannot Hear the Shape of a Drum", Bulletin of the American Mathematical Society 27 (1): 134–138, doi:10.1090/S0273-0979-1992-00289-6, http://www.ams.org/bull/1992-27-01/S0273-0979-1992-00289-6/home.html

- Ivrii, V. Ja. (1980), "The second term of the spectral asymptotics for a Laplace–Beltrami operator on manifolds with boundary", Funktsional. Anal. i Prilozhen 14 (2): 25–34 (In Russian).

- Kac, Mark (1966), "Can one hear the shape of a drum?", American Mathematical Monthly 73 (4, part 2): 1–23, doi:10.2307/2313748, JSTOR 2313748

- Lapidus, Michel L. (1991), "Can one hear the shape of a fractal drum? Partial resolution of the Weyl–Berry conjecture", Geometric analysis and computer graphics (Berkeley, CA, 1988), Math. Sci. Res. Inst. Publ. (New York: Springer) (17): 119–126

- Lapidus, Michel L. (1993), "Vibrations of fractal drums, the Riemann hypothesis, waves in fractal media, and the Weyl–Berry conjecture", in B. D. Sleeman and R. J. Jarvis, Ordinary and Partial Differential Equations, Vol IV, Proc. Twelfth Internat. Conf. (Dundee, Scotland,UK, June 1992), Pitman Research Notes in Math. Series, 289, London: Longman and Technical, pp. 126–209

- Lapidus, Michel L.; Pomerance, Carl (1993), "The Riemann zeta-function and the one-dimensional Weyl-Berry conjecture for fractal drums", Proc. London Math. Soc. (3) 66 (1): 41–69, doi:10.1112/plms/s3-66.1.41

- Lapidus, Michel L.; Pomerance, Carl (1996), "Counterexamples to the modified Weyl–Berry conjecture on fractal drums", Math. Proc. Cambridge Philos. Soc. 119 (1): 167–178, doi:10.1017/S0305004100074053

- Lapidus, M. L.; van Frankenhuysen, M. (2000), Fractal Geometry and Number Theory: Complex dimensions of fractal strings and zeros of zeta functions, Boston: Birkhauser. (Revised and enlarged second edition to appear in 2005.)

- Milnor, John (1964), "Eigenvalues of the Laplace operator on certain manifolds", Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America 51: 542ff

- Sunada, T. (1985), "Riemannian coverings and isospectral manifolds", Ann. Of Math. (2) 121 (1): 169–186, doi:10.2307/1971195, JSTOR 1971195

- Zelditch, S. (2000), "Spectral determination of analytic bi-axisymmetric plane domains", Geometric and Functional Analysis 10 (3): 628–677, doi:10.1007/PL00001633

External links

- Isospectral Drums by Toby Driscoll at the University of Delaware

- Some planar isospectral domains by Peter Buser, John Horton Conway, Peter Doyle, and Klaus-Dieter Semmler

- Drums That Sound Alike by Ivars Peterson at the Mathematical Association of America web site

- Weisstein, Eric W., "Isospectral Manifolds" from MathWorld.

- Benguria, Rafael D. (2001), "Dirichlet eigenvalue", in Hazewinkel, Michiel, Encyclopedia of Mathematics, Springer, ISBN 978-1556080104, http://www.encyclopediaofmath.org/index.php?title=d/d130170